|

Set in a depression

covering over 2000 sq. km., Bahariya Oasis is surrounded by

black hills made up of ferruginous quartzite and dolorite. Most

of the villages and cultivated land can be viewed from the top

of the 50-meter-high Jebel al-Mi'ysrah, together with the

massive dunes which threaten to engulf some of the older

settlements.

The Oasis was a major agricultural center during the Pharaonic

era, and has been famous for its wine as far back as the Middle

Kingdom. During the fourth century, the absence of Roman rule

and violent tribes in the area caused a decline as some of the

oasis was reclaimed by the sand. The Oasis was a major agricultural center during the Pharaonic

era, and has been famous for its wine as far back as the Middle

Kingdom. During the fourth century, the absence of Roman rule

and violent tribes in the area caused a decline as some of the

oasis was reclaimed by the sand.

Wildlife is plentiful, especially birds such as wheatears; crops

(which only cover a small percentage of the total area) include

dates, olives, apricots, rice and corn.

There are a number of springs in the area, some very hot, such

as Bir ar-Ramla but probably the best is Bir al-Ghaba, about 10

miles north east of Bawiti. There is also Bir al-Mattar, a cold

springs which poors into a concrete pool

Otherwise near the Oasis is the Black and White deserts, though

traveling to the White desert seems not practical from the

oasis. The Black Desert was formed through wind erosion as the

nearby volcanic mountains were spewed over the desert floor.

Finally, there are the ruins of a 17th Dynasty temple and

settlement, and nearby tombs where birds were buried.

Bawiti, Bahareya’s capital , is by far the largest village in

the Bahariya Oasis with some 30,000 inhabitants. The town center

is modern, while outside the center are mud-brick houses.

Recently, the town has received considerable press due to the

find of a huge (possibly the largest) necropolis of mommies from

the Greco-Roman era.

Over time, the Bahariya Oasis has had a number of different

names. It has been called the Northern Oasis, the Little Oasis,

Zeszes, Oassis Parva and the especially during the Christian

era, the Oasis of al-Bahnasa, along with various other names. Over time, the Bahariya Oasis has had a number of different

names. It has been called the Northern Oasis, the Little Oasis,

Zeszes, Oassis Parva and the especially during the Christian

era, the Oasis of al-Bahnasa, along with various other names.

Remains of stone tools found in the Bahariya oasis evidence the

existence of settlements in the area as early as the Paleolithic

Period.

Is seems that the Bahariya Oasis was originally inhabited by a

mix of people from the Nile Valley and Bedouins from Libya. At

that time, evidence suggests that the Oasis was much larger than

it is now, but no settlements dating to the Predynastic, Early

Dynastic or Old Kingdom have thus far been unearthed.

By the Middle Kingdom, Bahariya was known as Zeszes, and

definitely fell under the control of the Egyptian kings, though

only a single scarab (inscribed with the name of Senusret) from

that period has been found in Bahariya. Yet, documentary

evidence provides that both Amenemhet and Senusret II began to

pay considerable attention to the Oasis, probably to deflect

regular attacks from the Libyans. At that time, there must have

been large agricultural estates, large houses for the

landowners, and even military garrisons to keep marauders at

bay. Agriculture was, as it is now, of major importance to this

community, and wine, as well as other goods of the Oasis, made

their way from here to the Nile Valley by donkey caravans along

two different routes.

However, during the 15th Dynasty, when Egypt was under the rule

of the Hyksos kings from Palestine, there was a lapse in trade

with the Oasis, presumably because the trade routes were unsafe.

At that time, we find only one text that refers to the Oasis,

when King Kamose refers to it as DjesDjes, the word for the

region's famous wine.

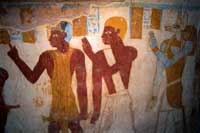

Under King Tuthmosis III, many improvements were made in the

Oasis, including new water wells. His reign marked an increase

in the local population. At this time, the Oasis was under the

control of Thinis (Abydos), to which they paid tribute. We find

visual evidence of this in the private tomb of Rekhmire, who was

Tuthmosis III's vizier. One scene portrays the people of the

Oasis, wearing striped kilts, presenting gifts of mats, hides

and wine. However, the Oasis apparently had at least a governor

who was a native of Bahariya, for the oldest tomb so far

discovered in the Oasis is that of Amenhotep Huy, where his

title is given as "Governor of the Northern Oasis". The tomb is

dated to the end of the 18th Dynasty or the beginning of the

19th. By the 19th Dynasty of Egypt's New Kingdom, the Bahariya

Oasis became even more important because of its mineral

abundance. Even today, the mining of iron ore continues to be a

vital industry. Even Ramesses II, in the Temple of Amun at Luxor,

refers to the Bahariya as a place of mining. Of course

agricultural products continued to be important in the Oasis,

including dates, grapes, figs, livestock and pigeons (for food). Under King Tuthmosis III, many improvements were made in the

Oasis, including new water wells. His reign marked an increase

in the local population. At this time, the Oasis was under the

control of Thinis (Abydos), to which they paid tribute. We find

visual evidence of this in the private tomb of Rekhmire, who was

Tuthmosis III's vizier. One scene portrays the people of the

Oasis, wearing striped kilts, presenting gifts of mats, hides

and wine. However, the Oasis apparently had at least a governor

who was a native of Bahariya, for the oldest tomb so far

discovered in the Oasis is that of Amenhotep Huy, where his

title is given as "Governor of the Northern Oasis". The tomb is

dated to the end of the 18th Dynasty or the beginning of the

19th. By the 19th Dynasty of Egypt's New Kingdom, the Bahariya

Oasis became even more important because of its mineral

abundance. Even today, the mining of iron ore continues to be a

vital industry. Even Ramesses II, in the Temple of Amun at Luxor,

refers to the Bahariya as a place of mining. Of course

agricultural products continued to be important in the Oasis,

including dates, grapes, figs, livestock and pigeons (for food).

During the 25th and 26th dynasties Bahariya Oasis flourished as

an important agricultural and trade center. Specifically, by the

26th Dynasty, Bahariya prospered with its own governors who were

natives of the oasis. They apparently continued to report to

Abydos, where there apparently remained a governor over all of

the Oasis. By the time of Ahmose II (570-526 BC), the importance

of the Bahariya Oasis was fully understood. He sent troops into

the Western Desert to defend Egyptian interests against the

Greeks and Libyans, and acted vigilantly to protect this Oasis.

To honor him, two temples were erected, along with a number of

chapels near Ain el-Muftella (near El Bawiti). These temples

were embellished even into Egypt's Persian period.

During the Persian period that followed a series of takeovers by

the Nubians and Assyrians, a strong military presence and

garrison were established in the Bahariya Oasis. They may have

been responsible for some of the antiquities that have been

attributed to the Romans. However, they could not stop the

conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great, once he decided to

make Egypt his own.

It is very possible that Alexandria the Great traveled through

the Bahariya Oasis on his way to the Oracle of Amun at Siwa. At

first, Egypt was a organized under a centrally controlled

government headed by Alexander's commander, Ptolemy, and the

Bahariya Oasis immediately began to prosper. Not only were trade

routes reestablished, but the Greeks used the Oasis to establish

control over the rest of the Western Desert. In fact, they set

up an extensive, permanent military garrison to protect the

trade routes. During the Roman and Greek Periods, we seem to

know more about the Bahariya Oasis than from any other period of

time. It was during the Greek period that the cemetery known as

the Valley of the Golden Mummies came into existence.

During the Greek period, we know that Thoth was worshiped in the

Oasis, particularly in his Ibis form, while Hathor is referred

to as the "Lady of Bahariya Oasis". Khonsu, the moon god and

Amun were both called "Lords of the Bahariya Oasis", though Amun

was dominant.

The Romans made many improvements within the Oasis, building an

impressive series of aqueducts and wells, several of which are

still used in Bawiti and Izza today. This oasis was important to

the Romans as a breadbasket, and we find many tombs dug into the

sides of the Bahariya mountains during Roman times. There were

public works projects, new agricultural communities were formed,

roads were cut, and thousands of mud-brick buildings were

constructed. The Romans made many improvements within the Oasis, building an

impressive series of aqueducts and wells, several of which are

still used in Bawiti and Izza today. This oasis was important to

the Romans as a breadbasket, and we find many tombs dug into the

sides of the Bahariya mountains during Roman times. There were

public works projects, new agricultural communities were formed,

roads were cut, and thousands of mud-brick buildings were

constructed.

During the Christian period, when Egypt continued under Roman

rule, Bahariya was known as the Oasis of al-Bahnasa. There are

many churches in the area, including a church named after Saint

Bartholomew. There was also a monastery that stood in Bawiti

called Dar al-Abras, the Lepers' Refuge, there had been crosses

engraved on the walls, paintings, and contained many old

writings. At that time the Christians called Bahariya Mari

Girgis (St. George).

Bahariya was known as the Northern Oasis, or sometimes as Waha

al-Khas during the early Islamic period. How exactly the

religious pecking order of the Bahariya was made up during the

Christian and Islamic periods is unclear, but it is evident that

the Oasis had a considerable Christian community until the 16th

or 17th century. Amir Ibn el-As, the commander of the Arab army

that conquered Egypt, sent troops to ensure political stability

within the Western Desert. During this period, the oasis

suffered considerably, as did most places in the Western Oasis;

sand dunes covered cultivated land, and the trade in wine was

abandoned due to the edicts of Islam. Taxes were now levied

against dates and olive oil. Much of this period is relatively

unknown to us, but the Fatimids, who had affiliations in Libya,

may have crossed the desert in the conquest of Egypt at Bahariya.

Muhammad Ali, often sited as the founder of modern Egypt, made

claim to the Bahariya Oasis, as early as 1813 and travelers

began to visit the area.

Today, Bahariya's history continues, more detailed than before.

Besides archaeologists who seem to have an ever increasing

interest in the Oasis, a genealogical history is also kept by

several Sheikhs. They not only record births, and deaths, but

also surprising events, such as an encounter with a jinn or

other supernatural creatures. Three books are kept, including

one in Bawiti, another in Mandisha and a third in the area of El

Haiz. Today, Bahariya's history continues, more detailed than before.

Besides archaeologists who seem to have an ever increasing

interest in the Oasis, a genealogical history is also kept by

several Sheikhs. They not only record births, and deaths, but

also surprising events, such as an encounter with a jinn or

other supernatural creatures. Three books are kept, including

one in Bawiti, another in Mandisha and a third in the area of El

Haiz.

Owing to a marked drop in agricultural land bought about by the

declining water table under Bahariya, the Oasis suffered a sharp

decline in population during the 1950s. It reached a level of no

more than about 6,000 residents, but by 1986, the population

increased to 20,000 and today there are about 27,000 people

living in Bahariya. This is mostly due to a new paved road

system established in 1973 over the old caravan routes, allowing

a better lifestyle as well as an increase in tourism. Yet the

Bahariya Oasis, though the closest to Cairo in kilometers,

remains the most distant in time. It has been slow to move into

the modern world, a facet that is changing, but for at least the

moment, this Oasis offers the visitor a step back in time into

medieval streets and a rare, ancient culture. |