|

El-Deir El-Bahari

Lying directly across the Nile from the Great Temple of Amun at

Karnak, the rock amphitheater of Deir el-Bahri provides a

natural focal point of the west bank terrain and an inviting

site for the temples of many rulers. The natural rock

amphitheater, a deep bay in the cliffs, was an important

religious and funerary site in the Theban area. Lying directly across the Nile from the Great Temple of Amun at

Karnak, the rock amphitheater of Deir el-Bahri provides a

natural focal point of the west bank terrain and an inviting

site for the temples of many rulers. The natural rock

amphitheater, a deep bay in the cliffs, was an important

religious and funerary site in the Theban area.

The remains of the temples of Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II,

Hatshepsut, and Tutmosis III, as well as private tombs dating to

those reigns and through to the Ptolemaic period can be found

here.

The most important private tombs at Deir el-Bahri are those of

Meketra, which contain many painted wooden funerary models from

the Middle Kingdom, and even the first recorded human-headed

canopic jar, and the tomb of Senenmut, Hatshepsut’s adviser and

tutor to her daughter..

Temple of

Nebhepetre Mentuhotep Temple of

Nebhepetre Mentuhotep

Nebhepetre Mentuhotep was the first ruler of the 11th Dynasty in

the Middle Kingdom. His temple was the first to be built in the

great bay of Deir el-Bahri.

It is smaller and not so well-preserved as is the later temple

built by Hatshepsut.

The front part of the temple was made of limestone and was

dedicated to Montu-Ra, local deity of Thebes before Amun.

The rear of the temple was made of sandstone and was the cult

center for the king.

Temple of

Tutmosis III Temple of

Tutmosis III

Tutmosis III, the successor to Hatshepsut, built a temple

complex here. It was only discovered in 1961.

The complex was built to Amun, as was a chapel to Hathor. The

structure was probably intended to receive the barque of Amun

during the Feast of the Valley, and thus would have replaced the

temple of Hatshepsut.

After a landslide seriously damaged the temple at the end of the

20th Dynasty, it was apparently abandoned. It then became a

quarry, and later, a cemetery for the nearby Coptic monastery.

Temple of

Hatshepsut Temple of

Hatshepsut

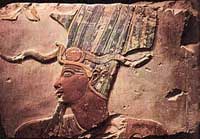

Hatshepsut was a woman who dared to challenge the tradition of

male kingship. She died from undisclosed causes after imposing

her will for a time. After her death, her name and memory

suffered attempted systematic obliteration.

The temple of Hatshepsut is the best-preserved of the three

complexes. Called by the people Djeser-djeseru, "sacred of

sacreds", Hatshepsut’s terraced and rock-cut temple is one of

the most impressive monuments of the west bank.

The mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut is one of the most

dramatically situated in the world; it is situated directly

against the rock face of Deir el-Bahri’s great rock bay, the

temple not only echoed the lines of the surrounding cliffs in

its design, but it seems a natural extension of the rock faces.

The queen's architect, Senenmut, designed it and set it at the

head of a valley overshadowed by the Peak of the Thebes, the

"Lover of Silence," where lived the goddess who presided over

the necropolis.

The approach to the temple was along a 121-foot wide, causeway,

sphinx-lined, that led from the valley to the pylons. These

pylons have now disappeared and ramps led from terrace to

terrace.

The porticoes on the lowest terrace are out of

proportion and coloring with the rest of the building. They were

restored in 1906 to protect the celebrated reliefs depicting the

transport of obelisks by barge to Karnak and the miraculous

birth of Queen Hatshepsut. Reliefs on the south side of the

middle terrace show the queen's expedition by way of the Red Sea

to Punt, the land of incense. Along the front of the upper

terrace, a line of large, gently smiling Osirid statues of the

queen looked out over the valley. In the shade of the colonnade

behind, brightly painted reliefs decorated the walls. Throughout

the temple, statues and sphinxes of the queen proliferated. Many

of them have been reconstructed, with patience and ingenuity,

from the thousands of smashed fragments found by the excavators;

some are now in the Cairo Museum, and others the Metropolitan

Museum of Art, New York The porticoes on the lowest terrace are out of

proportion and coloring with the rest of the building. They were

restored in 1906 to protect the celebrated reliefs depicting the

transport of obelisks by barge to Karnak and the miraculous

birth of Queen Hatshepsut. Reliefs on the south side of the

middle terrace show the queen's expedition by way of the Red Sea

to Punt, the land of incense. Along the front of the upper

terrace, a line of large, gently smiling Osirid statues of the

queen looked out over the valley. In the shade of the colonnade

behind, brightly painted reliefs decorated the walls. Throughout

the temple, statues and sphinxes of the queen proliferated. Many

of them have been reconstructed, with patience and ingenuity,

from the thousands of smashed fragments found by the excavators;

some are now in the Cairo Museum, and others the Metropolitan

Museum of Art, New York |